Parkinson’s disease dementia represents a significant and often challenging neurocognitive complication in individuals with established Parkinson’s disease (PD). While PD is most commonly thought of as a movement disorder, up to 40% or more of patients will develop dementia as the disease progresses. For clinical neuropsychologists, recognising, characterising, and differentiating Parkinson’s Disease Dementia is critical in clinical practice, shaping both patient care and support for families.

Defining Parkinson’s Disease Dementia #

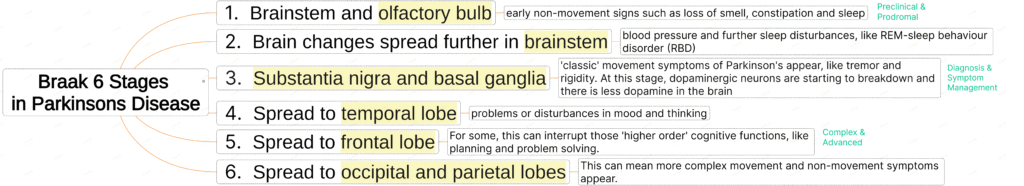

Parkinson’s Disease Dementia refers specifically to dementia that arises in the context of Parkinson’s disease, generally appearing at least one year after the onset of motor symptoms (whereas early cognitive and motor onset points towards dementia with Lewy bodies). The clinical syndrome is attributed to the spread of Lewy body pathology and the progressive involvement of dopaminergic and other neurotransmitter systems beyond the basal ganglia.

Pathophysiology of Parkinson’s Disease #

- Dopaminergic system degeneration: Loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra leads to the classic motor symptoms and underpins aspects of cognitive change, especially in attention and executive function.

- Widespread Lewy body (alpha-synuclein) pathology: Lewy bodies accumulate across subcortical and cortical brain regions, disrupting multiple neurotransmitter pathways.

- Cholinergic deficits: These contribute to cognitive, attentional, and neuropsychiatric symptoms.

- Overlap with Alzheimer’s pathology: Many cases, especially with older age, also have coexisting Alzheimer’s-type changes, influencing the cognitive profile.

Core Clinical Features of Parkinson’s Disease Dementia #

Parkinson’s disease dementia presents a distinct constellation of cognitive, behavioural, and neurological signs. Neuropsychological assessment helps to characterise both the neurocognitive profile and the progression.

Brain Imaging in Parkinson’s Disease #

Cognitive Profile in Parkinson’s Disease Dementia #

- Attention and processing speed: Slowed thinking (bradyphrenia), mental inflexibility, distractibility, and reduced mental stamina are prominent. Complex attention is affected early and severely.

- Executive function: Deficits in planning, goal-directed behaviour, set-shifting, and working memory are hallmarks. Patients may struggle with adapting to new situations, problem-solving, and dual-tasking.

- Memory impairment: While less severe than in Alzheimer’s disease, memory difficulties are common, typically involving the inefficient recall and retrieval of information. Recognition memory remains relatively better preserved, and external cues can often assist memory retrieval.

- Visuospatial deficits: Problems with spatial orientation, perception, and construction are frequent—sometimes profound—and may result in difficulties with driving, navigation, or recognising locations.

- Language: Generally preserved, though patients may exhibit reduced verbal fluency (both semantic and phonemic) and subtle word-finding problems, often related to executive dysfunction or slowness rather than primary language impairment.

Behavioural and Psychiatric Features in Parkinson’s Disease Dementia #

- Hallucinations and psychosis: Visual hallucinations, usually non-threatening, are common. Delusional thinking or misidentification can emerge, particularly in later stages.

- Apathy and depression: Reduced motivation and initiative are frequent and can be mistaken for depression or progressive cognitive decline.

- Anxiety and agitation: These can co-occur, often related to insight into declining abilities or fluctuating symptoms.

- Fluctuating cognition: Patients may have “good” and “bad” days, with periods of reduced alertness and confusion.

Motor and Neurological Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease Dementia #

Neuropsychologists must always interpret cognitive findings in the context of the motor symptoms of PD, which may include:

- Bradykinesia: Slowness of movement affecting test performance; can also affect mental speed.

- Tremor and rigidity: May interfere with writing, drawing, or manipulation during testing.

- Postural instability: Can contribute to falls and reduce willingness to engage in some test activities.

- Masked facies: Reduced facial expression may be mistakenly interpreted as lack of engagement or affective disturbance.

- Dysarthria and hypophonia: May affect verbal output and apparent fluency.

Progression and Course of Parkinson’s Disease Dementia #

- Gradual onset: Cognitive decline emerges years after the onset of parkinsonian motor symptoms, with insidious worsening over time.

- Fluctuations: Levels of performance may change from day to day based on medication effects (‘on-off’ phenomena), fatigue, or comorbid delirium.

- Coexisting features: Sleep disturbance, REM behaviour disorder, and autonomic dysfunction (orthostatic hypotension, constipation, urinary problems) are common and can impact cognition further.

Neuropsychological Assessment and Differential Diagnosis #

The Neuropsychologist’s Role in Assessment and Management #

Comprehensive Assessment #

- Test selection and interpretation: Use bradyphrenia- and motor-sensitive measures thoughtfully. Allow extra time and account for motor slowness in test administration and scoring.

- Functional assessment: Evaluate not only cognitive impairment but also its impact on daily living, independence, and safety.

- Differentiation: Detailed neuropsychological profiling, combined with medical history and imaging, supports separation of Parkinson’s Disease Dementia from DLB, AD, and vascular causes.

- Monitoring: Re-assessment can help detect progression, medication effects, or superimposed delirium.

Formulation and Communication #

- Contextualise findings: Integrate cognitive, emotional, behavioural, and physical data, considering premorbid functioning and comorbidities.

- Interdisciplinary collaboration: Work with neurologists, geriatricians, and allied health for diagnosis, care planning, and management.

Patient and Family Support #

- Education: Inform families about the nature of cognitive and psychiatric symptoms, realistic prognosis, and strategies for daily living.

- Compensatory techniques: Tailor strategies to help with attention, memory, and executive functions (e.g., external aids, simplified tasks, environmental cues).

- Psychological support: Screen for and support mood disorders, coping, and adjustment for both patients and carers.

Risk Management #

- Driving and safety: Assess the impact of cognitive decline on driving, medication management, finances, and risk of delirium or psychosis due to medication.

- Communicate risk: Help families and medical teams understand patient vulnerabilities and necessary supports.

Differential Diagnosis in Parkinson’s Disease Dementia #

For clinical neuropsychologists, distinguishing Parkinson’s Disease Dementia from other dementias is essential:

- Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): DLB is diagnosed when cognitive impairment occurs before or within one year of parkinsonism onset; Parkinson’s Disease Dementia is diagnosed when dementia develops after well-established Parkinson’s disease.

- Alzheimer’s disease: AD is dominated by memory impairment (rapid forgetting), typically spares attention and visuospatial skills early, and lacks prominent parkinsonism.

- Vascular dementia: Prominent stepwise decline, focal neurological signs, and a history of vascular risk factors.

- Other parkinsonian disorders: Progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy have distinct cognitive and motor features.

- Medication effects and depression: Anticholinergics, dopaminergic agents, or severe mood disturbance can mimic or exacerbate cognitive symptoms.

Practical Considerations for Clinical Neuropsychologists #

- Medication side-effects: Dopaminergic and other medications can improve motor symptoms but worsen psychosis or fluctuations.

- No curative treatment: Cholinesterase inhibitors may be trialled, especially for attentional or psychiatric symptoms, but benefits are often modest. Anticholinergic drugs should generally be avoided.

- Optimise daily function: Focus on managing environment, routines, and psychosocial supports—aiming to maximise independence and quality of life.

Conclusion #

Parkinson’s disease dementia is a complex syndrome requiring nuanced neuropsychological evaluation and support. The cognitive and psychiatric profile is dominated by executive dysfunction, attentional deficits, and profound visuospatial impairment, progressing on a backdrop of well-established parkinsonism. Clinical neuropsychologists are essential in assessment, differentiation, monitoring, and providing practical and emotional support for patients and their families, working as part of an integrated, multidisciplinary team to optimise outcomes in this challenging disorder.